Early in my career, I built a feature that was supposed to change everything.

The stakeholder was convinced. “This will transform how the team works,” they said. I took it at face value. We spent weeks on it. Good code, solid architecture, all the edge cases handled. Shipped it. Nobody used it.

The feature fixed a symptom, not the actual problem. By the time I’d finished building, someone else had solved the root cause a different way. The feature just sat there, working perfectly, doing nothing.

That experience stuck with me. I’d built exactly what was asked for without questioning whether it was the right thing to build.

AI makes this mistake easier to make. AI can generate specs, scaffold code, write tests. The gap between “someone suggests a feature” and “feature is built” keeps shrinking. But speed doesn’t help if you’re heading in the wrong direction.

How common is the wrong direction? Pendo analyzed 615 SaaS subscriptions and found 80% of features are rarely or never used. An average of 12% of features generate 80% of daily usage volume. They measured click frequency, so a compliance tool clicked once a quarter could still matter. But the pattern is clear. Most of what gets built does not get pulled into anyone’s week. Pendo 2019 Feature Adoption Report

A workshop Grounding your Product Strategy by Vidya Dinamani that I attended and Geoff Woods’ book, The AI-Driven Leader, both hit this point from different angles and changed how I work.

The backwards problem

There’s a line from Woods’ book:

“If you don’t understand your business problem, your business challenge, the market forces, and customer demand, then asking ‘How do we use AI?’ is the wrong question.”

I’d often get caught out by immediately starting to build. AI has made that instinct worse. It removed the friction that used to slow me down. Three sprints in, I hadn’t asked “is this the right problem?” I’d been too busy shipping.

Dinamani’s workshop turned this into something we can use AI to help understand problems before using it to build.

What Thought Partner means

Woods has a distinction, Thought Leader vs Thought Partner.

You’re the Thought Leader. You bring the specific situation, judgment about what matters, and the final decision.

AI is your Thought Partner. It brings more angles faster, questions you didn’t think to ask, and different ways to look at the problem.

It’s easy to give up the leader role. I’ve caught myself asking AI to solve a problem without giving context. Copy-pasting output without thinking. Letting AI set the direction instead of expanding on mine.

This framing helped me with stakeholder conversations too. A senior person says “build this,” and the instinct is to start. AI makes that faster. The feature is scoped and half-built before anyone asks whether it solves the right problem.

What I’ve started doing is running the assumption surfacer before those conversations. I’ll take the request, list what needs to be true for it to work, and bring the riskiest assumptions back to the stakeholder. It changes the conversation from “here’s why we shouldn’t build this” to “here are the two things we’d need to check first.” That’s an easier conversation to have. And sometimes the stakeholder spots a risk I missed, which makes the plan better for both of us.

How I use this now

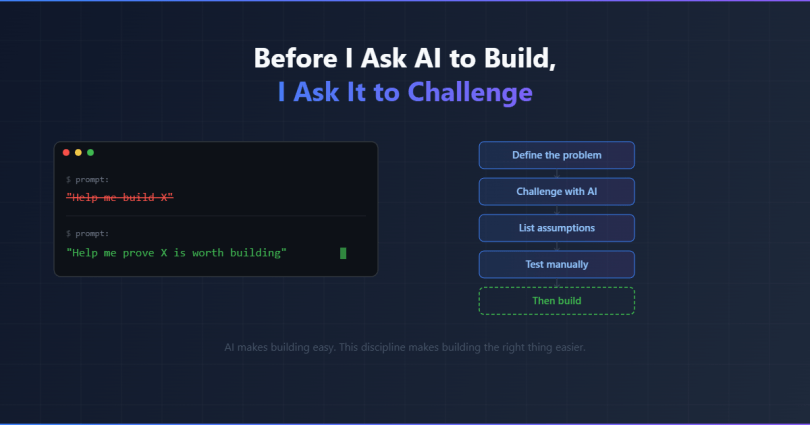

Before the workshop, my first prompt was usually “help me build X.”

Now it’s “help me understand whether X is the right thing to build.”

Instead of generating fixes, I’m stress-testing the problem. Instead of asking for code, I’m asking for questions.

Here’s what that looks like in practice.

Step 1: Define the problem without mentioning what to build

This was harder than I expected. I kept slipping into build language without noticing.

“Users need a dashboard.” That’s a build.

“Users need notifications.” Build.

“We should add an API.” Build.

What helped was describing who’s affected, what they’re trying to do, and what’s stopping them. No builds yet.

“First-time users abandon setup at step 3. We ask for information they don’t have ready.”

That’s testable. I could be wrong. But I can find out before building anything.

Step 2: Use AI to challenge the problem statement

Once I have a problem statement, I ask Claude to poke holes in it. Not to solve it, but to stress-test my understanding.

What am I assuming? What did I miss? Is this the real barrier, or a symptom of something else?

This is where hidden assumptions surface. The ones that feel so obvious I never thought to question them.

Step 3: List what must be true

Every product strategy rests on assumptions:

- Will people actually want this?

- Will they change their behaviour to use it?

- Is it worth building?

I used to jump straight to “can we build it?” AI makes building fast. But that’s the wrong question if nobody will use it.

I now ask Claude to list the assumptions behind my strategy, starting with the ones most likely to be wrong. Seeing them written out changes how I think about the risk.

The key for me is asking about behaviour change, not just desire. Users say they want something. That’s different from them actually using it. A meta-analysis of 47 experiments found that a medium-to-large shift in intention only produces a small-to-medium shift in actual behaviour . Webb & Sheeran, 2006 “Do they want better reporting?” and “will they log into a dashboard every week to check it?” are different questions with different answers.

There’s a question that’s easy to skip here: what are you not building? Every claim you choose to test means other problems stay unsolved for now. We can easily pick the most exciting one. We can add a line to the assumption surfacer prompt: “What am I deprioritizing by choosing this, and what’s the cost of leaving it unsolved?” Sometimes the opportunity cost changes the priority entirely.

Step 4: Test manually before building

Before writing any code, we can deliver the value by hand.

Say we’re considering a feature that aggregates customer feedback. Don’t build the aggregation tool. Pull the feedback together for one customer and hand it to them. Then watch what happens. Do they use it? Do they ask questions we didn’t expect? Do they change anything about how they work?

Alberto Savoia, Google’s first Engineering Director, calls this pretotyping: simulate the core experience of a product with the smallest possible investment before committing to building it. Pretotyping

Rule of thumb: if customers don’t change their behaviour when we deliver the value by hand, automating the delivery won’t change that.

The prompts I use

Those four steps are the thinking. Here are the prompts that drive them. They’re built on a pattern from the book: give AI a clear task, give context, ask it to interview you rather than just spit out answers.

The Problem Sharpener

I'm going to describe a problem I'm trying to solve. I want you to act asa Thought Partner - not to solve it, but to help me understand it better.After I describe the problem, interview me one question at a time to:- Clarify who exactly is affected and when- Surface barriers I might be glossing over- Identify assumptions I'm making without realizing it- Challenge whether I've framed the problem correctlyDon't suggest solutions. Help me see the problem more clearly.Here's the problem: [describe your problem]The Assumption Surfacer

I'm considering this product strategy: [describe what you're building and why].What assumptions am I making that must be true for this to work?Focus on:- Will people actually want this? Will they change their behaviour to use it?- Is it worth building? Does the value justify the cost?List 5-7 assumptions, starting with the ones most likely to be wrong.The Pre-Build Stress Test

Before I commit to building this, I want to pressure-test the idea.Context: [describe what you're planning to build and the problem it solves]Act as a skeptical but constructive advisor. Interview me one question ata time to find weaknesses in my thinking. Push back where my reasoningseems thin. Help me discover what I don't know before I invest in building.Same pattern in all three: I lead, AI partners. They ask for challenge, not answers.

What I’ve noticed:

- These work better before I’m emotionally invested in the design. Once I’ve spent a day on something, I defend it, weak assumptions and all.

- The interview format surfaces more than asking for a list upfront. Claude asks follow-up questions that catch things a one-shot prompt misses.

- I keep a running doc of assumptions I’ve surfaced. Patterns emerge. I keep underestimating how much users resist changing their workflows.

Putting it together

Here’s how it plays out. Say a team asks for a weekly email report. Sounds reasonable. The temptation is to start building it.

Run the request through the assumption surfacer first. Claude comes back with:

- People will open the email each week

- The data in the report will change their decisions

- Email is the right format (vs a dashboard, Slack message, or nothing)

- The team doesn’t already have this information somewhere else

Number 4 is worth checking. If the data already lives in a tool they use every day, the report just adds noise. The real problem might be that the data is hard to find, not that it’s missing.

This isn’t about being slow. It’s about being right before being fast. AI makes building so easy that the hard part isn’t execution anymore. The hard part is knowing what to execute..

That feature from early in my career? If I’d run these steps, I would have surfaced the key assumption: the problem will still exist when I ship. A conversation with the right people would have told me the root cause was already being addressed differently. I’d have built something else, or nothing at all.

AI makes building easy. This discipline makes building the right thing easier.

The workshop that sparked these ideas was run by Vidya Dinamani. The book I reference is “The AI-Driven Leader” by Geoff Woods, worth reading if you’re thinking about how AI changes strategic decisions. The AI-Driven Leader